Introduction

Nike started selling golf shoes in 1984, but golf was a minor component in Nike’s marketing juggernaut before Tiger Woods came aboard in 1996.

By 2000, Nike was selling balls and clubs as well as apparel and shoes, but even with the pull-through of Tiger’s then unsullied image yoked to Nike’s ingenious marketing, Nike’s golf equipment never caught on. Nike Golf always lagged in sales behind Callaway, Ping, Titleist and of course, TaylorMade, the brand owned by Nike’s fiercest rival, adidas.

It came as no surprise last year when Nike finally surrendered, announcing in August that it was getting out of the golf equipment business. Nike would still sell golf shoes and apparel, products consistent with its manufacturing and marketing savvy, but as an expert in golf retailing described it, “Nike was taking the least-ordered entrée off its menu.”

Not long after Nike’s announcement, adidas sold its golf equipment division for $425M USD, shedding TaylorMade, Ashworth and Adams Golf. In 2012, TaylorMade reported sales of $1.7 billion; by 2016, sales hovered around $900 million.

Rory McIlroy recently extended his contract to wear Nike apparel and shoes, reportedly for $100 million over ten years. Just one day after TaylorMade’s sale, McIlroy signed a deal to play its clubs for an equal amount over the same period. Golf retailing has an enormous investment in McIlroy. He’s known for his fitness, but that’s a lot of weight to carry.

What does it say about golf retailing’s future when the two greatest global brands in sportswear and athletic gear give up on golf equipment?

And why do they continue to spend massive sums on endorsement deals in a stagnant or shrinking market? What does that say about the golf industry’s future? Are there insights embedded in this commercial history which foretell golf’s retail fortunes?

To examine questions such as these, we need to look at both golf’s bigger picture and its smaller frames. The big picture must focus on: the power of golf’s global brands; China’s curious flirtation with golf and its dominant position in manufacturing golf equipment; and the global significance of golf tourism. Drilling down into the smaller frames, we want to examine changes in golf’s retail sector:

- the rise (and fall) of golf chain stores;

- golf equipment sales at big box sporting goods chains; and the demise of equipment sales in golf course pro shops, upending decades-long traditions.

- Above all, we need to examine the impact of internet-facilitated direct to consumer sales.

We start with China.

Part I: China. “Old Tom Morris, may I introduce you to Mr Mao Zedong”

Nearly twenty years ago, I participated in my first golf conference in China. Held in Guangzhou, it featured lectures and panel discussions by Chinese academics, government officials and western consultants. The academic discussions focused on golf’s place in Chinese society. Was golf a “royal sport”—and thus not consonant with modern Chinese values—or a “popular sport,” and thus consistent with Chinese ideals?

The scholarly conclusion was adroit, inventive and dogmatic. As far back as the Song dynasty (960–1279), the panel noted, a game called chuíwán—in translation, “hit ball”—was widespread. Not long after the conference, The New York Times published a story noting that “the Chinese have a compelling argument that it was they, indeed, who first played” golf. Historical research had cleared the way for golf’s acceptance into contemporary China.

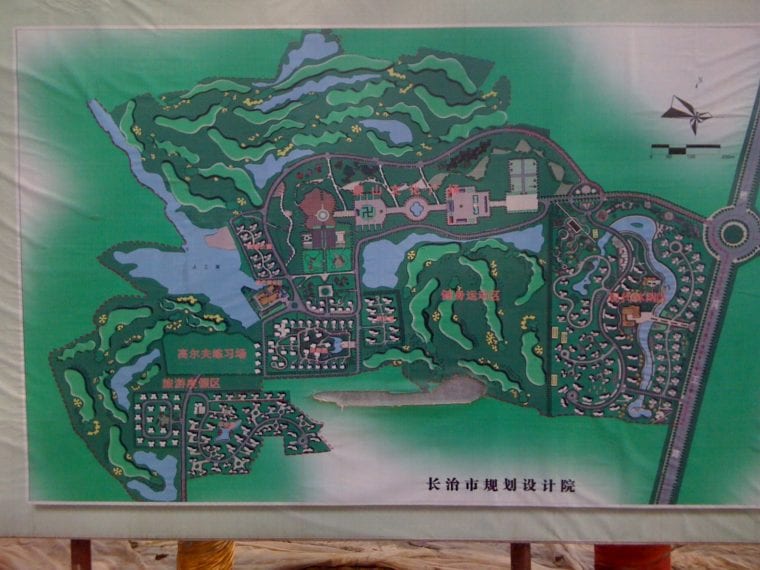

Government speakers at the conference emphasised golf’s ability to pull the Chinese economy forward rather than celebrating its cultural link to China’s past. Chinese golf courses were typically yoked to real estate development. The central government was pushing for high rates of growth throughout the country. Real estate developments were a key component of its strategy. The construction crane was China’s national bird. Golf course projects constituted a tiny but prominent element of the construction boom.

The official host of the 2001 golf conference, Mr Hu, stood well over six feet tall. He oversaw several sports bureaus, such as the governing bodies for ping pong, football, and tennis. His official title in English was “Minister of Small Balls.”

I spoke about golf’s potential for growth in China. As the CEO of Robert Trent Jones II, a leading global golf course architecture firm, I was involved with several Chinese projects already under construction. All the leading US and European golf course design firms were chasing Chinese clients, giddy with green visions. As the development pipeline filled with projects, memories of Japan’s exuberant embrace of golf development in the 1980s inspired hope that a similar scenario would unfold in China—but one avoiding any echo of the collapse of Japan’s real estate market, which has been a drag on the economy for decades.

China’s population then was 1.27 billion people, and its average annual per capita income was roughly $2,900. The average, however, concealed a more compelling number: nearly 65 million people in China’s rising middle class, just under 5% of the population. In 2000, China was the seventh-largest car market in the world, building and selling just over two million vehicles annually. The US market was then six times larger than China’s. China now makes and sells more cars than any other country.

China’s middle class was, therefore, the potential driver of golf’s expansion. Anyone with enough disposable income to buy a car (almost entirely cash purchases in China) would, I assumed, have the wherewithal to take up golf. Because playing golf was associated with status, given that only people with money and time could afford to play, golf’s potential was tremendous. If it grew at even a fraction of Japan or Korea or Thailand’s pace, golf in China would be colossal. Membership in a club—and most Chinese clubs were built on the US country club model, meaning they were not open for public play—was as important a milestone as buying an apartment or owning a car. Membership in a golf club announced success and was thus aspirational for young Chinese business and professional people.

My estimate of the number of courses China would “need” was based on a modest middle-class golf participation rate of 2%. If 1,500 golfers can sustain a course, then China’s middle class in 2001 could have supported 867 courses. That looks like a large number until you compare it to the USA, which has a quarter of China’s population, a middle class of 162 million people, and around 15,000 golf courses. America’s middle-class is a shrinking portion of the population, while China’s middle class continues to grow. McKinsey estimates China’s middle class now at 225 million people.

The 21st century promised great opportunities for golf in China. It was building some very good courses. It was identifying and training excellent young players. It was staging professional tournaments featuring the best players in the world. It was manufacturing most of the world’s golf equipment. It staged large and popular golf trade shows, which demonstrated a popular appetite for golf, especially among young urban professionals—exactly the class of people the golf industry in the West is desperate to attract. But in spite of those positive signs, the government nonetheless promulgated a policy banning golf course construction in 2004.

The government owns all the land in China. State-owned banks hold deposits placed in their care by a population with a savings rate above 30%, among the highest in the world. Developers would purchase development rights from the local governments with borrowed funds. The officials would, in turn, deposit the payments made to acquire development rights back into the banks. The developer borrowed again to finance construction. Consumers drew on their savings to buy houses and apartments. The money flowed back to the bank. The local government reported a politically advantageous high rate of economic growth to the central government. Everyone was happy.

Except that in some cases development could not proceed until the land was cleared—and in this case, clearing refers not to vegetation, but to people. In principal, the developers would pay occupants to move, or provide housing in a new location. This was presented as an overall improvement for the displaced, but it put pressure on rural people to migrate, which in turn fed the Chinese manufacturing sector’s demand for cheap labor.

Though officially forbidden, golf course construction continued openly for another decade. The government finally cracked down hard in 2014. Since then, about 115 Chinese courses have been shut down, converted to tree farms or other non-golf uses, leaving roughly 400 courses open—and the bulk of those are in the major cities, such as Beijing or Shanghai, or on Hainan Island, a designated tourism region.

China has moved from a low-wage manufacturing economy dependent on small margin exports to an economy providing higher value services and products requiring robust supply chains and skilled labor. China not only makes more cars than any other country, it makes airplanes, bullet trains and computers. Its shoppers embrace the internet. The government encourages consumer spending, eager to stimulate its citizens to spend more. China’s auto market has exploded. The Chinese are the world’s leading customers for smartphones—buying about a third of all sold.

Because it has excess manufacturing capacity, China can encourage low prices in its domestic market. Given that the government wants people to spend, coupled that with the fact that China produces most of the world’s golf equipment and has a large group of aspiring golfers, why hasn’t China done more officially to embrace golf?

Here’s where things get complicated. The official reasoning invokes food security, environmental concerns, and protection of the rights of the rural population. Premier Xi Jinping told party officials they cannot belong to golf clubs, which is pretty much a death sentence for golf, given that most of the people who play golf now either belong to the party or have close ties to it. That’s how you get ahead in China.

There’s no doubt that China’s air and water quality are atrocious, but golf plays a very little part if any in China’s pollution crisis. It’s the coal-fired power plants and the chemical factories and the overall fixation on economic growth that make breathing such a challenge in China’s cities. Rural waterways are used as convenient disposal sites for liquids of any type. Solid trash is also dumped in streams and rivers. Some golf courses have been built without appropriate scrutiny in China, and that should be condemned. Employing bioremediation in golf course construction, a proven success in the US, could help China address its environmental crisis.

But that’s a separate issue, in a way, from that of China’s role in the global golf market. In the US, Europe, and the rest of Asia, where golf is growing rapidly—with Thailand surpassing Spain as the world’s leading golf tourism destination, according to the World Tourism Organization—golf clubs and balls and bags and shoes and shirts and hats manufactured in China dominate the market, even if the brand names on the merchandise are mostly western.

We’ll examine the implications of China’s role in golf manufacturing in Part II of this series, The Retail Dilemma of Golf Brands.

In Part III, we will look at how creative companies, such as Columbia Sportswear, have responded to the changes to the retail environment brought about by the decline of brick and mortar stores and the growth of internet-based retail giants, such as Amazon and Alibaba.

John Strawn is a Director with Global Golf Advisors (GGA), the largest professional advisory services firm dedicated to the business of golf. John can be reached on jstrawn@globalgolfadvisors.com